About Informal Practices in Latin America: An introduction

Informal Practices in Latin America: Exploring the cultural and societal roots of informal behaviours

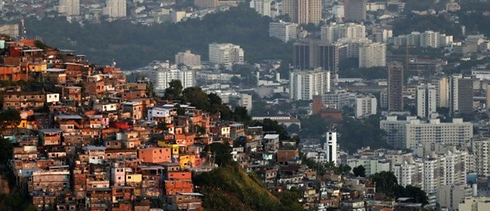

Relatively speaking, Latin American nation-states are somewhat weak and their democracies fragile (Centeno, 2002). Still today, political turmoil and popular outcry remain the norm for most Latin American countries. As a result, informality has become the necessary solution to everyday-problems.

Having lived in Latin American countries, all three of us experienced first-hand the prevalence of informality and its banality in the life of locals. Armed with the theoretical and analytical toolkit, we decided to explore a couple of common informal practices and make them available to the wider public via this website.

These informal practices (particularly in Latin America) generally evade the academic spotlight due to their intrinsically vernacular nature. By drawing upon the growing body of academic research in Latin America and using our own primary data collected by interviewing Latin Americans, we seek to bring these informal practices out from the shadows. The two main informal practices explored here are the Colombian concept of the “Rosca”, and Ecuadorian idea of a “Sapada”.

Ultimately, we hope this work will be provide a constructive addition to the Global Encyclopaedia of Informality and in doing so contribute to further studies into the world of Informal Practices.

In this first section of the website, I will provide an overview of the political and societal landscape of Latin American, exploring how it might impact the state-to-citizen relationship and therefore lead to informality. In the second part, I will shift my focus to policy- and attempt to highlight the implications and progresses being made with regards to reducing the pervasiveness of informal practices.

How Political Instability reveals the dysfunctional State-Citizen relationship

Perpetual political instability has plagued the region for the past 70 years (Young & Kent, 2013). Military coups, dictatorships and civil wars are all but too familiar for Latin Americans.

As a result of this instability, nation-states across the continent have struggled to develop the formal institutions required to drive economic development and bring people out of poverty. Whilst poverty rates have drastically improved in recent decades, formal institutions still lag behind. As we are about to discover, the lack of a strong state capable of providing citizens with reliable institutional frameworks has paved the way for the persistence of informal practices across nearly all spheres of socioeconomic activity.

Informality in the economic sector

Decades of dictatorships in Latin America since the 1950’s were followed by a profound economic crisis developed throughout the continent. As inflation skyrocketed, unemployment increased by 50% (Franco, 1999). This rapid fall in formal employment led millions to find ways of subsisting through informal methods. By 1990, the informal sector grew so considerably that it represented over 40% of the economically active population (International Labour Organisation, 2005).

Overtime, informal work has become socially accepted to the point where the existence of the informal economy has been legitimized and its development encouraged (Salinas et al., 2018)

Furthermore, tax evasion, encouraged by weak tax administrations, became rampant across the region. Despite continuous efforts, the neoliberal reforms mandated by the WTO did little to alleviate this sharp spike in informality.

The strong disparities that exist within the economic sector, and how vastly it is dominated by informality properly illustrates how informality has becoming progressively engrained in Latin American society. Indeed, it reveals the flaws of formal institutions in Latin American countries.

Whilst a lack of formal institutions provides less incentives for formal work, a similar pattern arises with when considering other forms of informal practices (a few of which we explore here).

Many, if not all countries in Latin America, akin to many countries where this type of pervasive informality occurs (Asia, Africa & developing countries in general) have problems with their “social contract”.

The pervasiveness of informality also means that over 240 million people in Latin America live without social protection.

Accessing job opportunities, healthcare etc… requires working ones way through informal channels.

Informal practices in day-to-day life

Cultural and societal practices have emerged as a solution to the absence of state interference and formal presence in the sphere of everyday life (Saavedra and Tommasi, 2007). Informal practices emerge as a ramification of the embittered relationship between individuals and the State (typically in charge of providing the formal institutional frameworks of society).

Social contracts play an important role in affecting the prevalence of informal practices. Loopholes and weak enforcement mean that there is more leniency for informal practices.

Chayote (literal meaning is a particular type of fruit) for example, is a term regularly used in Mexico to describe the money and gifts bestowed by politicians to prominent journalists in exchange for positive mediatic light. This is just one of the endless examples of unique terms used to describe the daily actions of many Latin Americans. This glossary provides an extensive account of voting-related informal practices in Mexico. So far, much of the academic literature surrounding informal practices in Latin America either focuses on the informality of the labour market or the top-down corruption taking place across the political landscape (between political and economic elites).

The inadequacy of the State to provide institutional frameworks within which to operate and sufficient public goods and services is essentially interwoven with the prevalence of informality.

Yet, the question remains. Should Latin American states hold back, letting these already engrained informal practices become part of its life, or should they attempt to eliminate these practices through policy and regulation (La Porta & Shleifer, 2014)?

Are these informal practices a subversive part of Latin American society which should be eradicated (an anomaly)? Or are they are instead a simple unavoidable part of Latin American society

Policy Implications

Whether policy-makers should attempt to reduce informality through direct reforms and regulations is still up for debate. In Latin America, Argentina has led the way in its attempts to reduce informality. Former Labour Minister Jorge Alberto Triaca led a number labour market reforms aimed at simplifying labour laws, defining clear guidelines for private employment agencies in which to operate and leading active labour market policies. Argentina’s focus on inclusion may pave the way for similar policies across Latin America aimed at promoting the access (and most of all integration) of citizens within society’s formal institutions.

As the graph below illustrates, GDP per capita tends to be greater where formality. The question remains however: Is this causality or correlation? If so, does GDP growth imply a reduction in informality, or vice-versa? And how do you accurately measure a country’s GDP if informality (inherently difficult to measure) itself plays an important part in the creation of wealth?

Figure 2: Informality and economic development (average rate of informal employment, in percentage) - Source

In conclusion, informal practices are embedded deeply within Latin American culture and seep through almost every social strata of its society. The truth is, informality emerges not so much as a cause of the defects of formal institutions, but as a solution to them (Ledeneva, 2008). Concomitantly, one could say that the priority for Latin American policy-makers should not so much be to repress these informal networks and practices, but to develop and meliorate the existing formal institutions so as to discourage the use of informality as a means of getting by.

Moreover, one of the main conclusions derived from our research is that whilst many concepts typically share the same meaning, the actual terms themselves are often local (i.e. bound to a specific geographic place) and culture specific. In fact, whilst coima encapsulates the idea of “” in Argentina, the same concept is called “” in Ecuador.

Developing an understanding of the deep-rootedness and ubiquity of certain informal practices is invaluable for academic research in informality, but also for providing States with the know-how to remedy this “short-circuiting” between the State and its citizens.

Reference list:

Biles, J.J., 2009. Informal work in Latin America: Competing perspectives and recent debates. Geography Compass, 3(1), pp.214-236.

Centeno, M.A., 2002. Blood and debt: War and the nation-state in Latin America. Penn State Press.

International Labor Organization. (2000). Labor overview: Latin America and the Caribbean. Lima,

Peru: ILO.

La Porta, R. and Shleifer, A., 2014. Informality and development. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(3), pp.109-26.

Ledeneva, A., 2008. Blat and guanxi: Informal practices in Russia and China. Comparative studies in society and history, 50(1), pp.118-144.

Salinas, A., Muffatto, M. and Alvarado, R., 2018. Informal institutions and informal entrepreneurial activity: new panel data evidence from Latin American countries. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 24(4), pp.1-17.

Saavedra, J. and Tommasi, M., 2007. Informality, the State and the social contract in Latin America: A preliminary exploration. International Labour Review, 146(3‐4), pp.279-309.

Scott, W.R., 2013. Institutions and organizations: Ideas, interests, and identities. Sage Publications.

Young, J.W. and Kent, J., 2013. International relations since 1945. Oxford University Press,18(5), pp.400-416.

Fig.1: Tax Revenues in Latin America and OECD Countries: Latin America's massive problem of tax compliance (which might explain the informality and contributes to socioeconomic inequalities) Source